Container Shipping: Past, Perils, and Future Resilience

Container shipping has long been the backbone of global trade, enabling efficient movement of goods across continents. But as the industry continues to evolve, it faces a growing set of challenges, from environmental pressures and operational risks to geopolitical disruption. Building resilience is now central to its future.

The insights below were explored in detail during ABL’s September Maritime Market Briefing, presented by Consultant Master Mariner Frazer Munro.

From break bulk to mega vessels

Before containerisation, cargo was shipped as break bulk—barrels, crates, and sacks manually loaded into ship holds. This method was slow, labour-intensive, and prone to damage and theft. Ships could spend weeks in port, making global trade inefficient and costly.

In 1956, American trucking entrepreneur Malcolm McLean launched the Ideal-X, the world’s first container vessel, a converted oil tanker that carried just 58 containers. The impact was revolutionary with loading costs dropping from around $6 per ton to just 16 cents. By the 1960s, standardised containers known as a Twenty-foot Equivalent unit (TEUs) and intermodal transport reshaped shipping, improving efficiency, security, and affordability.

The 1970s saw the adoption of the container begin to grow with purpose-built fully cellular container ships being built, and ports developing the container cranes to handle them. These vessels such as the Liverpool Bay class carried up to 2,500 TEU.

Through the 1980s and 1990s, ship sizes were constrained by the dimensions of the Panama Canal, about 32 metres, a design known as Panamax. But with China’s rise as a global exporter, larger vessels became viable. Maersk led the charge with the 8,000+ TEU Sovereign Maersk in 1997 and the 14,000+ TEU Emma Maersk in 2006. By the mid-2010s, Ultra Large Container Vessels (ULCVs) became the norm, with the Ever Alot breaking the 24,000 TEU barrier in 2022.

Modern risks and operational challenges

Extreme weather

Despite technological advances, container shipping faces persistent risks. Container losses at sea remain a concern, with spikes in recent years due to extreme weather. Diverted routes around the Cape of Good Hope, prompted by Red Sea security threats, increase exposure to rough seas and the likelihood of cargo loss.

Parametric rolling

Parametric rolling—a violent side-to-side motion triggered by specific wave conditions—is particularly dangerous for large container vessels. Though underreported, it can lead to catastrophic outcomes if not properly managed. Enhanced weather routing software and crew training are helping mitigate these risks.

Cargo securing gear

Container securing gear has also evolved, with automatic and semi-automatic twist locks replacing manual systems. However, these can release unintentionally in bad weather as the lifting forces used to release them could be replicated by the vessel’s motion in rough seas.

Fire

Fire risks are rising, often linked to misdeclared dangerous goods. In 2023, container fires occurred every 9 days according to statistics from Cargo Incident Notification System (CINS). Fires also had significant impact in the first six months of 2025 with the Nordic Association of Marine Insurers reporting that, of claims above $10 million, nearly 60% were fires, with four of those claims exceeding $20 million.

Lithium-ion batteries are a particular concern, with recent incidents off India’s coast resulting in fatalities and massive claims. Fires also cause environmental damage, with firefighting efforts releasing pollutants and microplastics into the sea.

Ongoing solutions

Detection and prevention technologies—such as thermal imaging and hydro-pen systems—are being deployed. Ports are enhancing inspection protocols, and the IMDG Code is mandating stricter training and enforcement. AI and blockchain tools are helping flag suspicious cargo bookings, while misdeclaration fees now range from around $15,000–$30,000 per incident.

Geopolitical threats and cyber resilience

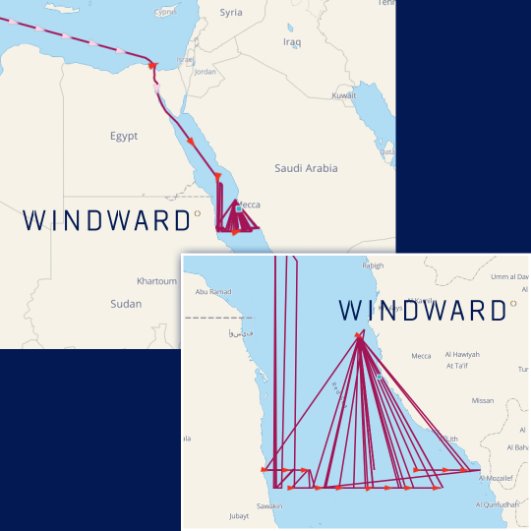

GPS jamming is an escalating threat, particularly in regions of geopolitical tension and conflict. It works by overpowering satellite signals with strong radio frequencies, disrupting navigation systems like AIS, GMDSS, autopilot, ECDIS, and radar. This creates a barrage of alarms on the bridge, overwhelming crews and compromising safety.

In May 2025, the MSC Antonia ran aground on a well-charted reef in the Red Sea, an incident linked to GPS jamming. In the Eastern Baltic, crews reported outages in satellite TV and mobile services, halting windfarm operations reliant as their dynamic positioning systems relied heavily on GPS.

Mitigation measures include updating software and firmware, securing network access, and implementing multi-layered navigation using traditional methods and inertial systems. Anti-jamming antennas are now available commercially, and companies are developing GPS jamming response plans. Cyber awareness training is also essential for crews and shore-based teams.

Green transition and future resilience

The IMO’s 2023 Revised Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Strategy targets net-zero emissions by 2050, with interim goals of 20–30% reduction of emissions by 2030 and 70–80% by 2040 (vs. 2008 levels). Progress is underway, but challenges remain.

In October 2024, 65% of container vessel orders were dual-fuel ships—303 LNG-fuelled and 216 methanol-powered—up from just 4% in 2018 (DNV). This indicates a strong and promising commitment to future-proofing fleets and reducing emissions. The Yara Birkeland, the world’s first zero-emission autonomous container vessel, operates in Norway with a 120 TEU capacity. Future upgrades include robotic mooring and AI-driven navigation.

Innovative propulsion methods are being trialled:

Nuclear propulsion: China unveiled plans for a 24,000 TEU nuclear-powered vessel in 2024, though regulatory and public concerns remain.

Wind-assisted propulsion: Rigid sails reduced fuel use by 3 tonnes/day in 2023 trials.

Smart containers with IoT (Internet of Things) tracking improve efficiency, reduce emissions, and enhance safety. They provide real-time data on location, temperature, humidity, and dangerous goods, helping optimise stowage and prevent bottlenecks.

While container volumes may grow 2–5x by 2050, according to a 2017 McKinsey report, vessel size increases may plateau. The law of diminishing returns, waterway depth limits (e.g. Malacca Strait, Suez Canal), and port infrastructure constraints mean future growth will focus on smarter design and sustainable operations.

Container shipping has come a long way, from barrels and crates to mega vessels and smart containers. But as the industry faces new and evolving threats, resilience, regulation, and innovation will be key to navigating the future.

ABL continues to support clients with expert insight and practical solutions, helping the maritime sector stay safe, sustainable, and prepared for what lies ahead.